In the Pasa Faho film, director Kalu Oji, stars Okey Bakassi and Tyson Palmer, and producers Mimo Mukii and Ivy Mutuku discuss fatherhood, identity, and why sometimes the most radical act isn’t fighting—it’s letting go.

PASA FAHO

Runtime: 86 minutes | Language: English, Igbo | Country: Australia

Director: Kalu Oji | Starring: Okey Bakassi, Tyson Palmer

Producers: Mimo Mukii, Ivy Mutuku | Production: TEN DAYS

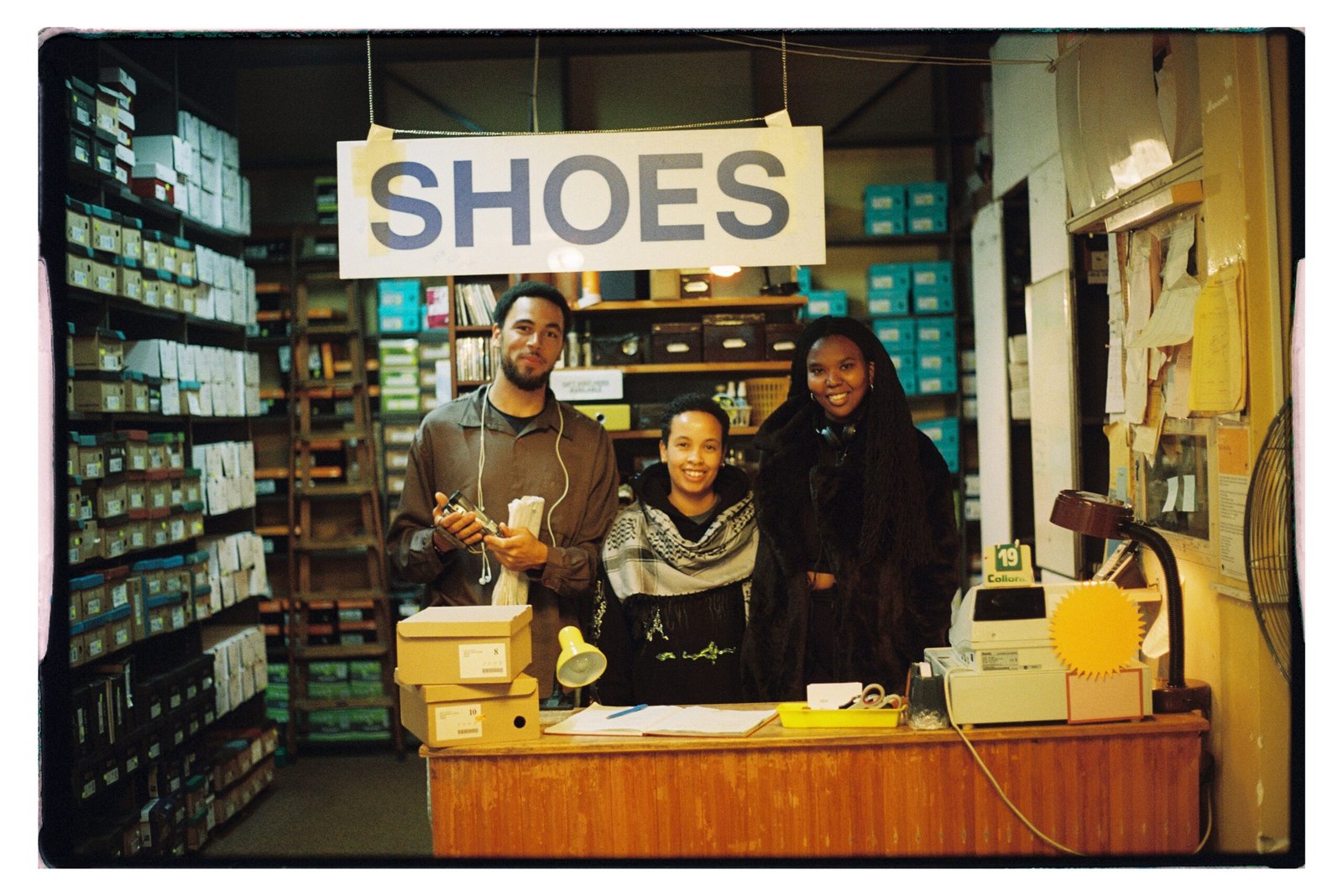

Photography: John. M Tubera

In the Pasa Faho film, director Kalu Oji’s feature debut doesn’t give us the immigrant story we expect. There’s no triumphant shop-saving, no Hail Mary that rescues the family business from developers. Instead, Oji offers something far more honest—and more difficult: a portrait of a man learning that sometimes the only way to keep your son is to release everything you thought made you strong.

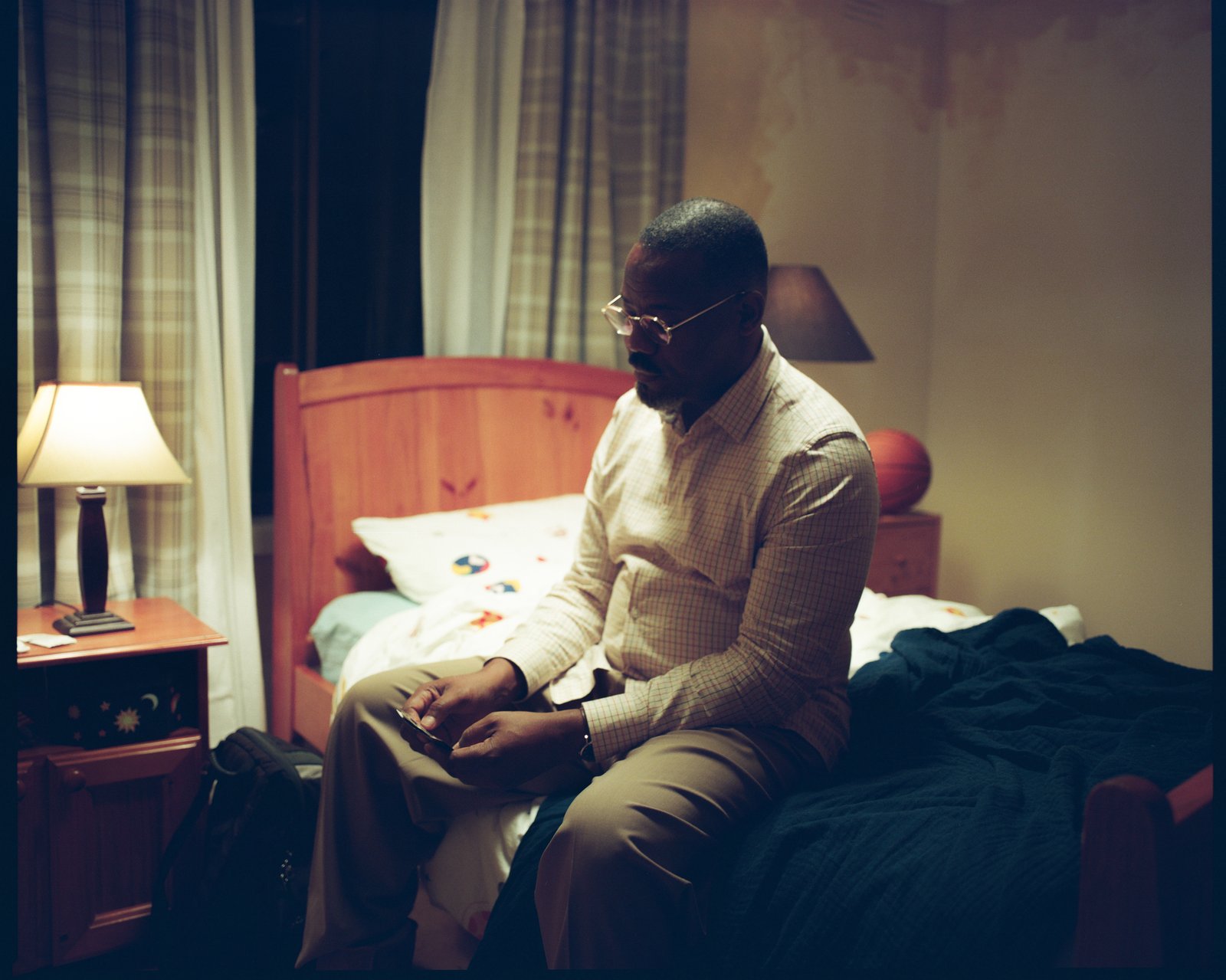

Azubuike (played by beloved Nigerian stand-up comedian Okey Bakassi) has run his shoe shop in suburban Melbourne for 20 years. When his estranged son Obinna (Tyson Palmer) arrives from interstate—where he’s been living with his white mother—Azubuike sees a chance to pass down what his father gave him: business principles, Igbo cultural wisdom, and the weight of manhood. Azubuike’s name means “the past is my strength” in Igbo. Obinna’s means “heart of his father.” But what happens when the heart no longer beats in rhythm with the past?

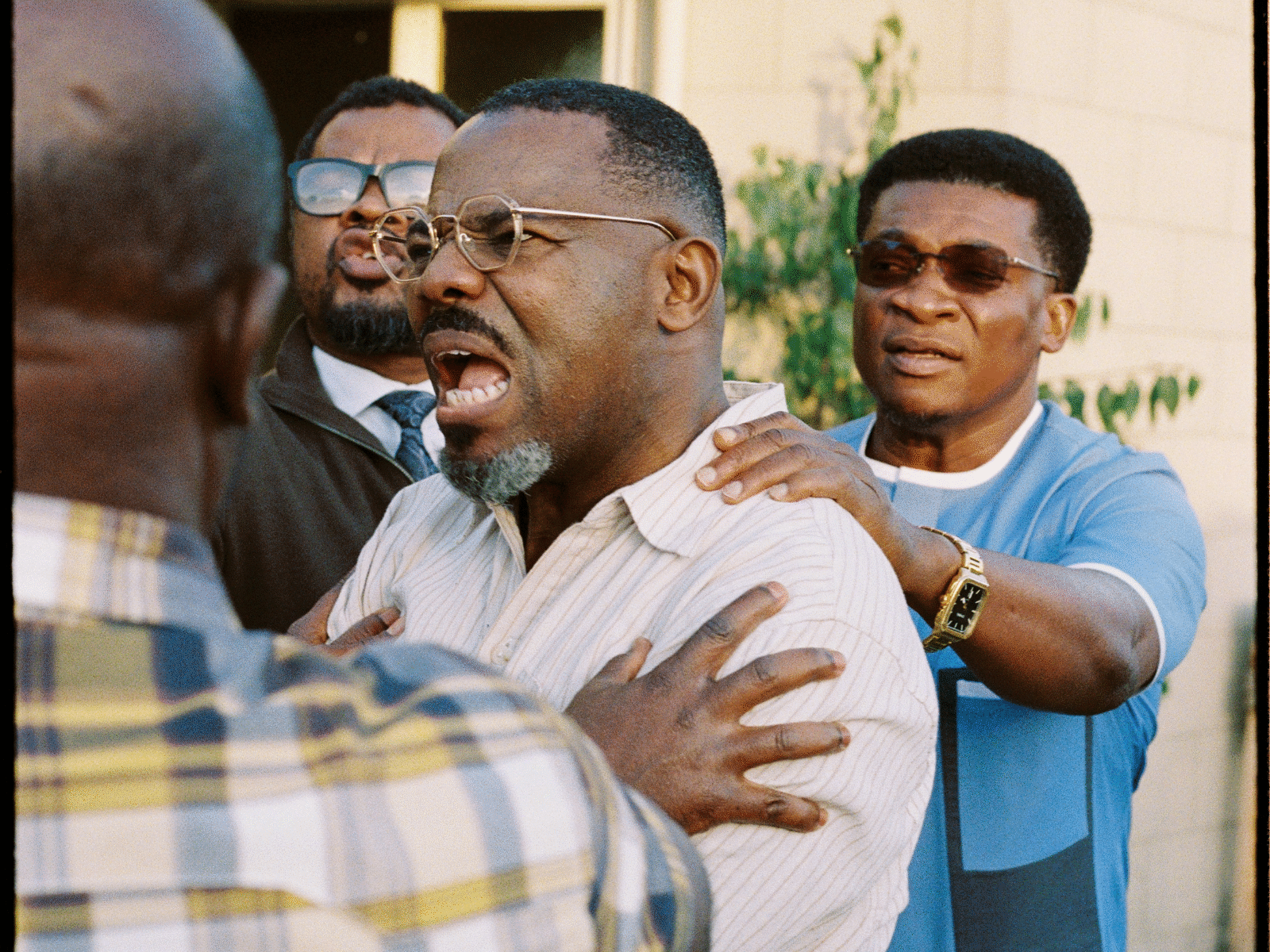

Then disaster strikes. The shop—his livelihood, his legacy, his proof of immigrant resilience—is threatened. The twist that deepens the wound: the buyer is a respected member of his own community. It’s betrayal from within, capitalism with a familiar face, and Azubuike must decide what matters more—winning the fight for his shop or winning back his son’s respect.

Here’s where Pasa Faho (the title is a play on “parts of a whole”) stakes its contrarian claim: What if the real victory isn’t saving what you’ve built, but surrendering the grip on how you define success? What if strength looks less like standing your ground and more like learning when to let go?

A backyard exchange mirrors a cultural chasm, 12-year-old Obinna insists the goat is a companion. His father, Azubuike, sees celebratory dinner. It’s a small moment in Pasa Faho that captures everything about the distance between an immigrant father determined to preserve Igbo traditions and his Australian-raised son who has learned to suppress the things that mark him as different.

After a sold-out Australian premiere at Melbourne International Film Festival—where Time Out Australia named it one of the festival’s ten best films—the 86-minute drama heads to Chicago International Film Festival for its international premiere on October 25. Critics have embraced its “tender” and “gently funny” approach to African-Australian life. ScreenHub Australia called it “beautiful, tender, and so well-acted… this gem of an Australian film should go on your watchlist straight away,” while FilmInk described it as “a moving and gently funny portrait” that refuses the trauma-only narratives often expected of diaspora stories.

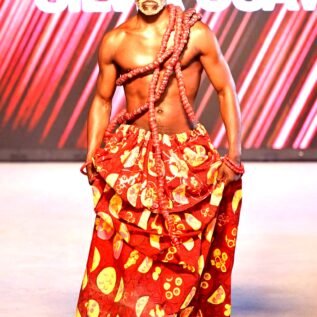

Oji’s debut, supported by MIFF’s Premiere Fund and produced by Mimo Mukii and Ivy Mutuku through TEN DAYS, is a vibrant tribute to Melbourne’s Igbo community and a meditation on the impossible mathematics of belonging: How do you pass on your values when the world your son inherits demands he subtract parts of himself to fit in?

We sat down with director Kalu Oji, stars Okey Bakassi and Tyson Palmer, and producers Mimo Mukii and Ivy Mutuku to discuss the making of Pasa Faho, the complexities of intergenerational diaspora storytelling, and why sometimes the most radical act a father can perform isn’t fighting—it’s letting go.

The Conversation

On the Vision

TIME AFRICA: Pasa Faho means “parts of a whole”—what inspired this title, and how does it reflect the themes you wanted to explore in the film?

Kalu Oji: A feeling of incompleteness; an understanding of one’s position in a community much larger than any individual; the parts of ourselves that fragment and change; a disjointed family unit; the diaspora and the connection it maintains to a global identity.

Pasa Faho is an imagined phrase that’s come to take on a lot of weight since making the film. All of these ideas were at the heart of the very first draft, though for a long time I thought this title was purely a placeholder. I was waiting for something more poignant, more fitting, to arise. Over time these two made-up words became very poignant, and very fitting. They came to represent everything we had set out to explore, and more of what we found along the way.

TIME AFRICA: The relationship between Azubuike and Obinna sits at the heart of the film—shaped by pride, quiet expectations, and a period of separation. What drew you to this particular story of disconnection and re-connection between an immigrant father and his assimilated son?

Kalu Oji: It’s a story that sits very close to my heart, and a truth that I see in many of the people around me. When I set out to make this film I was aware that it might take a long, long time. And so these were the questions I was grappling with; the themes and ideas I was most drawn to. Australia colours these experiences with such specificity, joy, and complexity. I hadn’t seen that on film before. I wanted to capture it; archive it.

TIME AFRICA: As a producer, what made you want to invest in Pasa Faho? What about this story felt urgent or necessary, especially within the context of African diaspora storytelling?

Mimo Mukii: Pasa Faho is the first scripted feature film to be written, directed, and produced by African-Australians, whilst also starring African and African-Australian actors. In the context of African diaspora storytelling, it is a privilege and a responsibility to be able to contribute to global African diaspora stories from an Australian perspective. I produce films that I would want to watch but haven’t seen made yet, and this is that film.

On Craft & Performance

TIME AFRICA: You’ve played countless roles over three decades in Nollywood. What resonated with you about Azubuike’s story, and how did you approach bringing him to life?

Okey Bakassi: What resonated with me about Azubuike’s story is the fact that it’s so close to real life for a lot of Nigerians who have families abroad. The challenge they face, especially trying to raise their children abroad to understand the culture and tradition of their ancestry while living in a foreign culture—it is tough.

I find parts of my own personal story in the Azubuike story because my wife and children live abroad while I live and work in Nigeria. In Igbo culture, the son continues the lineage. So you want to transfer your knowledge, your family history and tradition while trying to navigate the influence of the environment he’s growing in abroad. My real-life experience is what made stepping into the Azubuike character easier

TIME AFRICA: Okey Bakassi is a legend in Nollywood with 30+ years in the industry. What made him the right choice for Azubuike, and what did he bring to the role that surprised you?

Kalu Oji: We spent a long time casting this film, especially for the role of Azubuike. The decision to approach Okey came only a few months before production, and after about a year of casting and workshopping across Australia.

What made me feel he was the right choice, and what excited me most seeing him work on set, was the lightness he brought Azubuike to life with. I believe there’s a version of Azubuike who’s much more stoic, less accessible. Okey had this balance of warmth and charm, but because of his experience and skillset, he was able to access those somber, more heartbreaking emotions as well. He captured the complexity beautifully.

TIME AFRICA: As a young actor, what drew you to this role, and how did you approach portraying Obinna’s internal conflict?

Tyson Palmer: What drew me to this role was how I related to Obinna—being from a mixed-race family, having also been in situations dealing with cultural differences, and with the issues my dad and I had at times. Obinna and I were similar in many ways.

The internal conflict and the emotions I had to show were very familiar. I totally related and understood how he felt, so it was easier to portray. Working with Okey made a big difference as well—he is so talented as an actor, so it helped me being able to bounce off him during the emotional scenes.

TIME AFRICA: What was it like working opposite a Nollywood legend with 30+ years of experience, and how did you two build that on-screen relationship?

Tyson Palmer: First day meeting Okey I was so nervous and worried about messing up and “Will I be good enough?” I just thought, do your best and show him what you can do. Made it a lot easier that Kalu had organized for Okey and I to spend time together before we went into filming. Our first day we played pool, had a really nice time. Okey was heaps of fun and so easy to talk to—we just seemed to click.

The on-screen relationship felt easy right from the start. Okey was like a real father figure to me. He taught me so much about acting and the industry. Total respect!

TIME AFRICA: The father-son relationship with Tyson Palmer is the emotional core of the film. How did you build that on-screen dynamic, especially given the character’s estrangement?

Okey Bakassi: Fortunately, we had time during rehearsals to bond. I used that opportunity first of all to connect with him on a personal level before filming actually started. He is a kid who is very talented, and it made the connection easy. I am also a father with a son who is within his age bracket, and I have a very good relationship with my son. It made communication with Tyson seamless.

On Cultural Specificity

TIME AFRICA: There’s a moment where father and son clash over whether a pet goat is a cherished companion or dinner—a perfect metaphor for their cultural divide. How did you approach depicting these small but loaded moments of tradition versus assimilation?

Kalu Oji: A lot of these moments came quite naturally, either from experiences I’ve had or from anecdotes I’ve heard from people around me. The film is quite ‘everyday.’ I’d set out to make it that way—a small story that provided the space to explore big ideas. The specificity of moments such as these is what was key to giving it the richness it needed.

TIME AFRICA: What was it like filming the goat scene, and what do you think it reveals about Obinna’s perspective?

Tyson Palmer: Loved the goat scenes—hanging out with the goat was fun!

I think the scene really made the differences in the African/Australian cultures obvious to Obinna. He looked at the goat as a cute pet, whereas Okey believed it had to be killed for food. Obinna really struggled with having to kill the goat—I mean that was his friend. So after, it put a lot of strain on their relationship, very confusing time for Obinna. But in the end, I think he began to understand where his dad was coming from.

TIME AFRICA: The impending sale of Azubuike’s shop becomes a pressure point in the story. How does this subplot mirror the larger themes of displacement and belonging?

Kalu Oji: The dispute over Azubuike’s shop speaks to the heart of the film—it’s about home, identity, and what happens when these foundations are disrupted. The shop is more than just his livelihood; it’s his anchor, his sense of self, and his connection to community. It’s also the vessel that he wants to use to teach Obinna. Its loss mirrors the realities of displacement and gentrification that we see everywhere, especially in cities like Melbourne. When the things that once defined us begin to fade, we’re forced to look inwards—where home becomes less about geography and more about memory and connection.

On Production & Independence

TIME AFRICA: Pasa Faho is an independent feature—what were some of the unique challenges of bringing this story to life, and how did you and the team overcome them?

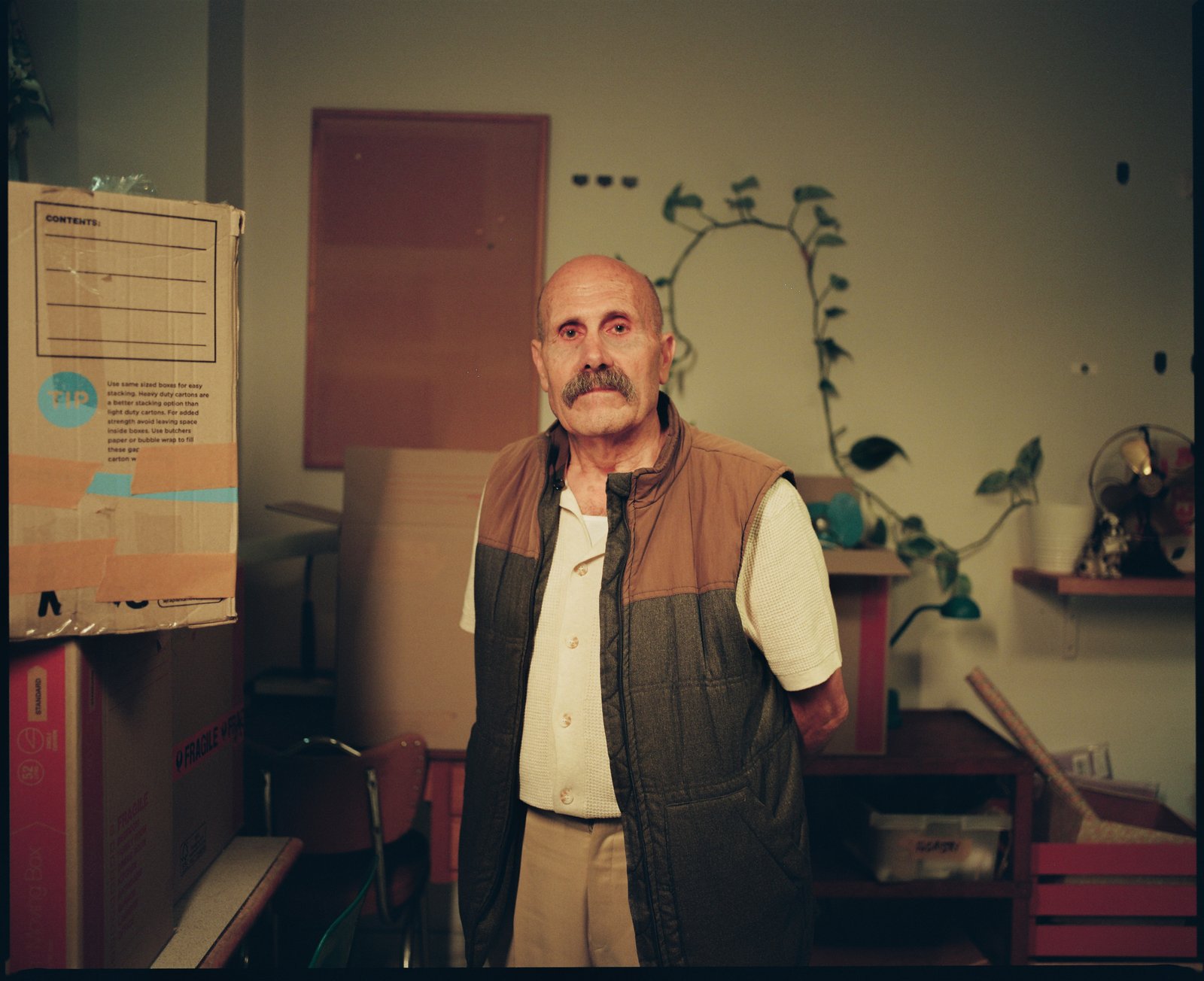

Mimo Mukii: It is always hard to make your first feature, as it is a risk to investors and funding bodies to invest in people with less experience. So we had to prove to stakeholders that we are capable of making and delivering a feature film. A unique challenge for this film is that we needed Igbo-speaking actors, which is hard to find in Australia. So we cast all of our supporting roles from the Igbo-Australian community, and the director worked with them to make sure they were able to shine on screen in their first acting roles.

TIME AFRICA: Kalu Oji is a first-time feature director with Pasa Faho. What was it like collaborating with him to bring his vision to the screen, and what surprised you most about his directorial approach?

Ivy Mutuku: Collaborating with Kalu, a collaborator and friend, on his first feature was an inspiring experience. From the outset, his vision for Pasa Faho was deeply grounded in nurturing truth, which shaped every creative choice. What impressed me most was his openness and vulnerability—he welcomed collaboration and trusted his team while remaining firmly anchored to the story’s heart. Kalu balanced conviction with curiosity, knowing when to lead decisively and when to let moments unfold naturally. That blend of sensitivity, precision, and confidence not only elevated the film but also created a space where creativity could truly thrive throughout production.

TIME AFRICA: As a producer, how did you approach ensuring the film’s themes of identity, belonging, and capitalism’s impact on immigrant communities were handled with authenticity and nuance?

Ivy Mutuku: My approach was centered on ensuring that the film’s exploration of identity and belonging felt deeply authentic and layered. From the beginning, we focused on collaboration and intentionality, working closely with Kalu to interrogate story choices and ensure they reflected lived realities rather than surface-level narratives. We engaged in ongoing conversations with individuals whose experiences mirrored those on screen, grounding the film’s emotional truth in real-world perspectives.

Authenticity also guided our casting and production decisions. We prioritized performers and crew members with shared cultural backgrounds, creating space for their insights to shape character dynamics and storytelling. Community members were integral to the process, helping us capture nuances—from language and ritual to visual detail—that give the world of the film its depth. Ultimately, our role was to hold space for complexity: to resist simplification and ensure the narrative spoke within immigrant experience rather than merely about it.

On Legacy & Impact

TIME AFRICA: Pasa Faho has been described as “moving and gently funny”—not the trauma-heavy narrative often expected of African diaspora stories. Why was it important to tell this story with tenderness and humor?

Kalu Oji: The films I’ve felt most affected by often exist in this space—for Black diasporic experiences and otherwise. I knew I wanted this story to be told with warmth, for it to be an enjoyable watch whilst at the same time presenting themes and ideas that opened the door for conversation and critical reflection.

TIME AFRICA: What do you hope audiences—especially young diaspora viewers—take away from Obinna’s journey?

Tyson Palmer: Don’t let cultural differences define your relationships. Go in with an open mind—every culture brings with it something different and unique, so be fair, reach a compromise when it comes to differences or beliefs. You don’t have to fit into the norms of just one culture, mix it up. We are special and lucky to be a part of two cultures. Life will never be boring.

TIME AFRICA: You and Mimo are both producers committed to African and diaspora storytelling. What responsibility do you feel producers have in shaping which stories get told and how they’re told—especially in the independent film space?

Ivy Mutuku: As producers committed to diaspora storytelling, we see our role as both creative and cultural stewards. The choices we make—which stories to back, whose voices to amplify, and how narratives are shaped—directly influence how our communities are seen and remembered. In the independent space, that responsibility is even greater. It’s about protecting authenticity while pushing for bold, complex portrayals that challenge stereotypes and expand global perspectives. Ultimately, producing isn’t just about getting films made—it’s about shaping cultural memory, creating space for truth, and ensuring our stories are told with care and intention for future generations.

Behinde The Scenes (Exclusive)

TIME AFRICA: After a sold-out Australian premiere at Melbourne International Film Festival and now heading to Chicago for the international premiere, what does this festival journey mean for the film—and what do you hope international audiences discover in Pasa Faho?

Kalu Oji: Celebration. Inspiration. Reflection.

Closing

Pasa Faho arrives at a moment when African diaspora cinema is redefining what success looks like—not just in box office numbers or festival laurels, but in the stories we choose to tell and how we choose to tell them. Kalu Oji’s debut refuses easy answers, choosing instead to sit in the uncomfortable space where love and tradition collide, where strength might mean surrender, and where home is less a place than a negotiation between past and present.

The film makes its international premiere at the 61st Chicago International Film Festival on October 25, 2025, with screenings at AMC NewCity 14 (1500 N. Clybourn Ave.), Music Box Theatre (3733 N. Southport Ave.), and Gene Siskel Film Center (164 N. State St.). Tickets range from $17–$25 and are available at chicagofilmfestival.com.

For more information about the film and upcoming screenings, visit Here

Read also: Efosa Ojomo on Innovation in Africa) — exploring how African thinkers are redefining global narratives.

PASA FAHO

Runtime: 86 minutes | Language: English, Igbo | Country: Australia

Director: Kalu Oji | Starring: Okey Bakassi, Tyson Palmer

Producers: Mimo Mukii, Ivy Mutuku | Production: TEN DAYS

Photography: John. M Tubera

Editorial Coverage in Partnership with Conscious Living PR

Featured Interview | TIME AFRICA Network

Editorial Standards: This interview maintains TIME AFRICA’s commitment to culturally specific,

authentic storytelling that amplifies African and AfroNouveau voices with integrity and depth.

© 2025 TIME AFRICA Network. All Rights Reserved.

For permissions and reprints: editorial@timeafrica.org

For Stories | Editorials | Coverage: placements@timeafrica.org

Atlanta | Lagos | Nairobi | London